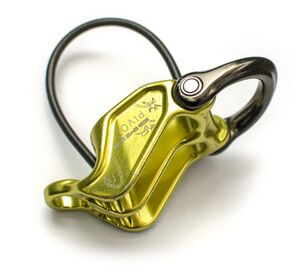

Tuber (Tubular belay device)

Tubular belay devices are the most commonly used belay devices for training of advanced climbing and rescue techniques, multipitching, and management of twin/double ropes. In some countries/clubs, they have been replaced by assisted tubular belay devices in single-pitch trainings. They are prohibited in some gyms due to the alleged security concerns (for details, see the security concerns section).

Review state This page has not been reviewed yet (review state explanation). |

Belaying from the harness

Slack taking

Slack feeding

General risks

Always hold/control the break strand with at least one hand and keep the break strand downwards unless giving or taking the slack. Keep your hand at least a few centimeters from the belay device to avoid pinching of the skin. Do not lift your hand too high (above the device) while giving the slack. One of the commonly seen bad habits while belaying is keeping the belay hand raised for a prolonged period of time.

Always hold the break strand downwards unless feeding/taking the rope Feed or take the rope from the front of the device Not holding the break strand can result in fatal injuries Holding the break hand too close to the tuber leads to a risk of pinching the skin of the break hand index finger. Do not lift the break hand excessively high during the break strand manipulation. Do not leave the hand in the elevated position if not taking or giving the slack.

Belaying at the anchor

Belaying the second climber

Belaying the lead climber

While belaying from the anchor, redirect the rope in a way that it points upwards even in a case of a fall. Usually an unlocked D-shaped carabiner is used. This redirection can be also in some cases built by a quickdraw placed in the second bolt of the anchor if the carabiner is short and the bolt is placed high enough. Once the lead climber makes two secure running protections on the route, the redirection is removed.

Belaying from harness at the anchor

During belay from harness at the anchor point, redirect the rope through the anchor till the first two pieces of the running protection are placed.

Anchor-belay risks

Belaying at the anchor brings additional risks on top of the general risks. Unlike during belay at a ground level, during anchor belay, climber can get below the tuber level during a fall. As illustrated below, if the climber would fall before the first running protection is placed, the tuber would not block as both the break strand and the live strand would be pointed the same direction.

Abseiling

Please refer to the separate abseiling page.

Tuber as an ascender

Due to its self-arresting nature in the guide mode, tubular belay devices can be used as an ascender,[1] effectively replacing for example garda hitch in self-rescue from crevasses.

Security concerns

Disclaimer This section reflects both subjective opinions and the positions of various alpine clubs. Qualified readers are encouraged to form their own judgment, or to follow the recommendations of recognized organizations. Unqualified readers are pointed to their club rules/recommendations. The aim here is not to prescribe one device over another, but to present different perspectives, so that climbers can make their own informed and responsible decisions. Neither Karl, nor any other contributor to this article promotes or discourages the use of specific devices; the responsibility lies fully with the climber and belayer. |

With non-assisted belay devices, the brake hand is the single point of failure. If the rope is released, a fall will not be slowed-down. While this carries inherent risk (if you let go, you let go), many climbers value these devices because they provide clear, immediate feedback on correct technique which helps to reinforce good habits. Also feeding the slack is except of a few cases smoother than with assisted-breaking devices.

Assisted belay devices, on the other hand, offer an additional layer of security, as the device itself can often stop a fall even if the break hand is not on position. This can reduce the likelihood of accidents. At the same time, the added security may also allow incorrect handling to go unnoticed and, over time, weaken safe habits as seen even among experienced users.[2]

The German Alpine Club (DAV) study from 2016 once again indicated more accidents with non-assisted tubular devices than with assisted devices, though most accidents were still traced back to incorrect use (burned hands).[3] Following these findings, gyms and clubs in Germany and the Netherlands began to strongly recommend assisted belay devices, or even banned the non-assisted ones. Yet, for instance a study conducted in 2019 year showed that Megajul is statistically more dangerous than a non-assisted tubular device.[4] While this is obviously caused by a very small sample size of accidents, it shows that user experience and handling technique may matter more than the device type. Affordability may also play a role, as non-assisted devices might have been chosen by newcomers as a starter option. As newcomers are less experienced, it is therefore reasonable to expect that they have a higher accident risk. Also in the same study, it has been shown that during bouldering there is approximately 10 times higher chance of an accident needing an ambulance when compared to a climbing hall (per hour of activity), showing climbing as generally a safer option. This ratio increased over 20 times in 2022.[5]

Different alpine clubs highlight different aspects. For instance the education commission of the Czech Alpine Club (ČHS),[6] highlights non-assisted devices for the way they build good habits, yet at the same time recommends assisted devices operated in a same way as the non-assisted ones for youth and newcomers.

There are reported severe accidents both for "letting go" while using non-assisted belay device[7] and for reckless handling of an assisted belay device.[2] However, most of the accidents occur not while belaying, but during abseiling (30%).[8][9] For this reason, good technique, clear communication and training in real conditions (fatigue resistance) remain the most critical safety priorities, regardless of the device used. Ultimately, the choice of the belay device is best made consciously and in agreement between belayer and climber as they are the one who carry the most imminent consequences of that choice.

References

- ↑ Godino, John. "Transformers! Your ATC belay device is also an ascender". alpinesavvy. Alpinesavvy LLC. Archived from the original on 28 November 2024. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hard is Easy (2 March 2025). Coach Nearly Kills Pro Climber – GriGri Incident Analysis. Hard is Easy. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV); KLEVER Kletterhallenverbandes (September 22, 2017). "Kletterhallenunfallstatistik 2016" (PDF). alpenverein.de. Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV); KLEVER Kletterhallenverbandes (November 5, 2020). "Kletterhallenunfallstatistik 2019" (PDF). alpenverein.de. Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV); KLEVER Kletterhallenverbandes (September 26, 2023). "Kletterhallenunfallstatistik 2022" (PDF). alpenverein.de. Deutschen Alpenverein (DAV). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Brodský, Břetislav; Vogel, Jiří; Hron, Michael; Tkáč, Lukáš; Kříž, Karel; Adámková, Michaela (13 August 2024). "Doporučení pro použití jistítek ve výuce (recommendation for using belay devices in teaching)" (PDF). Horosvaz.cz. Český horolezecký svaz. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Corrigan, Kevin. "A Series Of Unfortunate Events—A Fortunate Groundfall Landing". Climbing.com. Outside Interactive, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Hess, Rob (2012). "Know the Ropes: Rappelling". American Alpine club. The American Alpine Journal (AAJ). Archived from the original on 22 May 2025. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Warning - Raw footage of fatal rappel failure (end knot(s) seem absent): Balin, Miller; Cheyenne, Jørdan (4 October 2025). Live stream footage of the young man that fell Oct 1st, 2025 - Bailin Miller. Facebook - True Crime, Mysteries, Morbid Events & More. Retrieved 5 October 2025.